|

Goose Creek was the name of a Post Office located in a store in what was known

as Old Town (Texas Avenue area) and was physically moved by the inhabitants of

New Town, so they could name their city Goose Creek. Goose Creek was the name of a Post Office located in a store in what was known

as Old Town (Texas Avenue area) and was physically moved by the inhabitants of

New Town, so they could name their city Goose Creek.

Oil was discovered in 1908 at the mouth of Goose Creek and Tabbs Bay and became

known as the famous Goose Creek Oil Fields.

Oil was discovered in 1908 at the mouth of Goose Creek and Tabbs Bay and became

known as the famous Goose Creek Oil Fields.

The Goose Creek Oil Field became the first off-shore oil drilling in the state.

The Goose Creek Oil Field became the first off-shore oil drilling in the state.

Goose Creek was 2 miles from Baytown (Lee College area) and separated from Pelly by

the Southern

Pacific Railroad Tracks and a drainage ditch.

Goose Creek was 2 miles from Baytown (Lee College area) and separated from Pelly by

the Southern

Pacific Railroad Tracks and a drainage ditch.

Confederate Naval Works of Goose Creek

was established in the 1850's by brothers Captain Henry

Chubb and his brother Henry. Possibly 6 ships were built here and used to

support the South in the Civil War.

Read about it here!

Confederate Naval Works of Goose Creek

was established in the 1850's by brothers Captain Henry

Chubb and his brother Henry. Possibly 6 ships were built here and used to

support the South in the Civil War.

Read about it here!

Houses in New Town had to be constructed of brick, or stucco. Plots of land

were well laid out by Ross S. Sterling, a Chambers County store owner.

Houses in New Town had to be constructed of brick, or stucco. Plots of land

were well laid out by Ross S. Sterling, a Chambers County store owner.

Goose Creek incorporated in April 1919. It's business district was the hub of

the Tri-Cities and was the Texas Avenue area.

Goose Creek incorporated in April 1919. It's business district was the hub of

the Tri-Cities and was the Texas Avenue area.

In 1928, the city of Goose Creek covered only three-fourths of a square mile,

but had a population of 5000.

In 1928, the city of Goose Creek covered only three-fourths of a square mile,

but had a population of 5000.

In March 1947, after a census was taken of Goose Creek (9,928), the city folded

into Pelly/Baytown (11,030) and officially ceased to exist and took the name

Pelly.

In March 1947, after a census was taken of Goose Creek (9,928), the city folded

into Pelly/Baytown (11,030) and officially ceased to exist and took the name

Pelly.

The first Mayor of Goose Creek was C. Q. "Kid" Alexander.

The first Mayor of Goose Creek was C. Q. "Kid" Alexander.

See the photos of

Goose

Creek here!

See the photos of

Goose

Creek here!

The Brunson theater and the Decker Drive-In were both

owned by local merchant Howard E. Brunson.

The Brunson theater and the Decker Drive-In were both

owned by local merchant Howard E. Brunson.

|

Name of Goose Creek will live on

By Wanda Orton Mar 22, 2024

While Goose Creek stream is not extremely deep, flowing lazily

toward the Houston Ship Channel, its name dips deeply into history –

and controversy.

I was attending Baytown Junior High in the late 1940s during the

hot-tempered feud concerning what to call the newly consolidated

Tri-Cities of Baytown, Pelly and Goose Creek. Naturally, we kids

favored the name Baytown while our chief rivals, the Horace Mann

Junior High kids, cheered for the name of Goose Creek. Standing a

stone’s throw from Goose Creek city limits, the Horace Mann campus

actually was grounded in Pelly.

When anyone spoke against naming the new city Pelly, the highly

respected former Pelly Mayor Fred Pelly’s feelings were not hurt. He

made it clear he wanted to stay out of the name-calling and didn’t

want to pick a favorite. However, when pushed, he admitted liking

the name Baytown.

Meanwhile, the Baytown/Goose Creek debate raged on. Baytownians

claimed their town was older – as far back as the 1850s – and

therefore deserved the honor. “No!” responded the Goose Creekers.

“Our town is older! That was the name going back to Dr. Harvey

Whiting’s time as far back as the Texas Revolution, the 1830s.”

Somehow, the Indian Connection came up with the recollection of an

old story. Centuries ago, according to the legend, Indians prowling

the area discovered the creek and named it Goose Creek. They saw

many geese floating on and flying over the waterway.

I’ve wondered about that. Totally different from the civilized

Cherokee and other smart tribes, the Karankawas were not the most

literate tribe in Texas history. It’s doubtful they spoke English

and knew how to utter even two little words such as Goose and Creek.

As well as the name advocates for Goose Creek or Baytown, the

controversy attracted independents, the free thinkers opting for

alternatives. How about Point Sterling or Lee City? Or Whiting or

Scott Burg? Oak Tree? And – preceding an industrial complex with

that name – Bay Port?

Voter acceptance of the new city charter in 1948, including the name

Baytown, ended the discussion officially, but not emotionally. Hard

feelings, at least from the Goose Creek side, remained. For a while,

it seemed as though the whole matter was déjà vu all over again as

school trustees struggled with the issue of retaining the name Goose

Creek for the district or renaming it Baytown.

A talking point for Baytown was the Baytown Refinery of Humble Oil &

Refining Co. (now Exxon Mobil) being known worldwide. A company

tanker named Baytown even circled the globe, gliding by foreign

tankers arriving at or departing from the Baytown Docks.

Goose Creekers argued that the district always had that name. It had

historical – plus sentimental – value. A name change also would

cause a ton of paperwork, reorganizing and confusion. And would Lee

College, then governed by the public school system, have to change

its name? Throughout the city, some necessary changes were being

made with the purpose of avoiding confusion. Examples: Goose Creek

First Baptist was becoming Memorial Baptist because there already

was a Baytown First Baptist … Goose Creek Street became North Main…

Goose Creek Hospital, Baytown Hospital … not to mention many

business places that updated their name to Baytown.

Surprisingly, though the district keeping its name, several teacher

and parent-teacher organizations have adopting the name of Baytown.

By now, locals may never have heard about the conflict between

Baytown and Goose Creek. I remember it because I was there – an

impressionable adolescent hearing a whole lot of arguing and

agonizing connected with our town’s name. Since I was born and

raised in Baytown, you probably know what side I was on.

Thankfully, I have mellowed out through the years. I have a deeper

understanding of why the Goose Creek loyalists felt so strongly

about their town and its identity. Goose Creek was their community,

their history. They had family members and friends who attended or

remembered the original Goose Creek High School, housed in the

building that later became the original Horace Mann Junior High.

Be proud, Goose Creek Memorial High School. Your name draws

attention to an important part of our history – the ability to work

together in spite of past differences. That’s the way it should be –

all for one and one for all – Baytown, Goose Creek and Pelly.

In the meantime, good ol’ Goose Creek stream, like Old Man River,

keeps rolling along …

Wanda Orton is a retired managing editor of The Sun. She can be

reached at [email protected], Attention: Wanda Orton

|

|

Goose

Creek TX goes away back

Used by permission of Wanda

Orton

Long

before incorporating as a city and becoming a part of the Tri-Cities

that included Pelly and Baytown, it was known as Goose Creek.

Proof is in

a letter written in 1836 by Dr. Harvey Whiting, who gave his address

as Goose Creek. Published a century later in the La Grange Journal,

the letter was written to Col. James Morgan about two weeks after

the battle at San Jacinto.

Whiting

wanted to tell his side of the story in regard to a brief but

desperate trip to Morgan’s Point to consult with Mexican Army Gen.

Santa Anna and Col. Juan Almonte. Before the battle at San Jacinto

on April 21, 1836, the Mexican troops headquartered at Morgan’s

Point.

You may know

that story. While Morgan was on military duty in Galveston,

fortifying the island for a possible invasion, the Mexican Army

invaded his own turf. Before they left, the troops cleaned out

Morgan’s warehouse, taking enough provisions to last a war time.

Moreover, Gen. Santa Anna added Morgan’s pretty housekeeper Emily

West (a.k.a. Emily Morgan, the Yellow Rose of Texas) to their

caravan.

Worried

about the safety of his family, Whiting decided to row his boat over

to Morgan’s Point for a little talk. All he wanted from the Mexican

Army was assurance his family would be safe.

FYI,

Whiting’s home and medical office were located in the vicinity of

present-day Bicentennial Park. All of that land later acquired by

the Pruett family – including the old oak tree on Texas Avenue --

originally belonged to Whiting.

After Santa

Anna promised not to kill his family, Whiting returned home to Goose

Creek. Mission accomplished.

However,

there were repercussions. Rumors began to circulate that Whiting was

in cahoots with the Mexican Army. His loyalty was questioned,

especially by rabble-rouser David Kokernot, who called Whiting an

old thief – and even worse, a Tory!

Though he

never fought in the Texan Army, Whiting did his part for the war

effort. Risking his life, he went to Lynchburg to save important

documents from the home of Republic of Texas President David G.

Burnet. He may have been a pacifist, but he was neither a thief nor

Tory.

In his

letter to Morgan, he aimed to make all that clear.

Until

researching the history of the Tri-Cities the other day -- prepping

for a story about the 97th anniversary of the city of

Goose Creek -- I didn’t know an entire community went by that name

long, long ago.

I should

have known.

In my history files in a

folder labeled city of Goose Creek, I had overlooked a faded

newspaper clipping from the Houston Chronicle describing the Whiting

letter, dateline Goose Creek, May 3, 1836.

Houston Wade, a Houston

Chronicle reader in 1937, provided that newspaper with information

from the La Grange Journal about the Whiting letter. He was

responding to a story in the Chronicle by Chester Rogers about the

origin of the name Goose Creek. Rogers had written that Indians

roaming this area named the stream Goose Creek.

The Indians really

started something – didn’t they? Their designation for a stream

inspired the naming of a settlement, then a city, hospital, school

district, country club, myriad business places and most recently,

Goose Creek Memorial High School.

What’s in a name?

In the case of Goose Creek, a whole lot of local history.

|

|

Goose Creek, the early

years, remembered

Used by permission of Wanda

Orton

The late Dr. Richard Woods wrote an

inspirational book about how to make friends -- the subject of

Wednesday's column -- but, as far as I know, the retired Baytown

dentist never authored a book about local history.

He could have. Having grown up on downtown

Texas Avenue where his father, John Lynn Woods, owned a pharmacy,

Dr. Woods was an eye-witness to Baytown history long before this

entire city was known as Baytown. The original, incorporated Goose

Creek claimed Texas Avenue, and the Woods pharmacy was called the

Goose Creek Pharmacy. Goose Creek represented part of the Tri-Cities

along with incorporated Pelly and unincorporated Baytown.

The Woods business stood at 126 W. Texas

across the street from a competitor, Herring's Drug Store, owned by

Garrett Herring.

John Lynn Woods, drawn by reports of the

oil boom in the Goose Creek field, moved to Pelly in 1917 and set up

shop.

With the city of Goose Creek thriving in

commercial and residential development, Woods decided in 1925 to

relocate his pharmacy to Texas Avenue. Dr. G.A. Lillie of Goose

Creek and Dr. John Bevil of Beaumont were his business partners

until he bought them out.

Richard Woods helped his father at work and

his mother at home by running errands, first riding over the

Tri-Cities on his bicycle and then driving the family car at the age

of 8. That's right - 8.

Once, when I was quizzing him about local

history, he described his father's place of business. He said round

tables filled the center of the building all the way from the front

to the back where the drug department was located. There were

old-style chairs, the type seen today in some ice cream parlors.

Ceiling fans whirled above the tables to keep the customers cool.

A fire in 1935 and another one in 1940

destroyed the building but following each fire, the drug store was

remodeled and modernized. Eventually booths replaced the tables. In

addition, customers had the option of bar stools at the lunch

counter.

Complete meals were served, and Dr. Woods

even recalled the price. For 25 cents, a customer could buy a meal

consisting of a meat, three veggies, a drink and dessert. Later,

when the price was increased to 35 cents, customers complained.

Dr. Woods also remembered a young man who

ran the lunch counter in the early years. That would be Harold

Scarborough, who went on to become a successful pharmacist and owner

of his own business, lastly on Market in old Baytown.

John Lynn Woods opened his drug store door

every day at 7 a.m. and locked up at 10 p.m. In addition to filling

prescriptions throughout the day, he managed the whole store and

kept the books with a quill-type pen.

Dr. Woods, continuing his review of

downtown in the old days, said Culpepper's Furniture Store occupied

the northwest corner of Texas and Ashbel. The second floor of the

building housed a hospital manned by medical doctors William Brooks,

C.H. Langford and L.A. Hankins, who later built the Goose Creek

Hospital on West Defee next to the Del Monte Hotel.

Just south of Culpepper's on Ashbel was Dr.

N.L. Dudley's ear-nose-throat clinic and hospital. Dr. H.I. Davis

eventually bought this structure and practiced there for many years.

East of the Goose Creek Pharmacy was the

American Barber Shop, Dr. Woods said, noting that the late Dr.

Herbert Duke came for his shave at 8 a.m. every morning,

administered by a barber named Duke Jones.

Lillie-Duke Hospital, at West Pearce and

Ashbel, was owned by Dr. Duke and John Lynn Woods' former business

partner, Dr. Lillie.

|

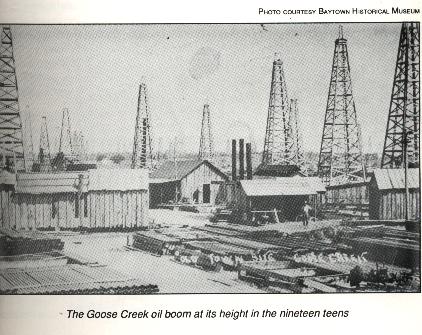

| GOOSE CREEK

OILFIELD. The first offshore drilling for oil in Texas occurred

along Goose Creek in southeast Harris County, twenty-one miles

southeast of Houston on Galveston Bay. In 1903 John I. Gaillard

noticed bubbles popping to the surface of the water at the point

where the creek empties into the bay. With a match he confirmed that

the bubbles were natural gas, a strong indication of oil deposits.

Royal Matthews leased the Gaillard property and drilled for 2½ years

but could not bring in a continuously producing well.

Not until a Houston-based

syndicate, Goose Creek Production Company, drilled on the marsh of

the bay was oil found, on June 2, 1908, at 1,600 feet. On June 13

the Houston syndicate sold out to Producers Oil Company, a

subsidiary of the Texas Company. After drilling twenty dry holes in

two years they abandoned the field. The American Petroleum Company,

new holders of a lease on Gaillard's land, finally drilled close to

the shore. On August 23, 1916, contractor Charles Mitchell brought

in a 10,000-barrel gusher at 2,017 feet. Initially the well produced

8,000 barrels daily, a quantity indicating that Goose Creek was a

large oilfield.

The community changed overnight as men rushed to

obtain leases, drill wells, and build derricks. Tents were

everywhere, teams hauled heavy equipment, and barges brought lumber

and pipe from Houston. Within two months the well leveled off to 300

barrels a day, but by December 1916 drilling along the shores of

Goose Creek, Tabbs Bay, and Black Duck Bay had raised production to

5,000 barrels daily. The flow of the average well drilled in 1917

was 1,181 barrels a day. The largest well of the field was Sweet 16

of the Simms-Sinclair Company, which came in on August 4, 1917,

gushing 35,000 barrels a day from a depth of 3,050 feet. This well

stayed out of control for three days before the crew could close it.

World War II oil prices of $1.35 a barrel encouraged Humble Oil and

Refining Company and Gulf Production Company to try offshore

drilling. The Goose Creek field reached its peak annual production

of 8,923,635 barrels with onshore and offshore drilling by 1918.

In 1917 Ross S. Sterling a

founder and president of Humble Oil (now Exxon, U.S.A.), bought the

Southern Pipe Line Company to route oil from the field to the

Houston Ship Channel Two 7,000-foot lines of four-inch pipe crossed

Black Duck Bay storage tanks and a wharf on Hog Island in the

channel. Since Goose Creek oilfield was a prospective long-term

producer, Humble constructed its major refinery, which was completed

by April 21, 1921, adjacent to the field and named the plant and

townsite Baytown. The Dayton-Goose Creek Railroad Company, built in

1918, connected the refinery to the Goose Creek field.

The Goose Creek field is a

deep-seated salt dome with overlying beds slightly arched; its

discovery spurred exploration for deep-seated domes, and led to the

discovery of some of the largest oilfields in the United States.

Production declined from 1918 until 1943, when it was only 388,250

barrels; 2,146,450 barrels was produced in 1965. Principal operators

in the field in 1984 were Exxon, Gulf Oil, the Monsanto Company,

Coastal Oil and Gas Corporation, and Enderli Oil. The total

production of the field in 1983 was 366,225 barrels. The first

Gaillard well and the Sims Sweet 16 were still producing in 1984. In

1990 the field's 192 wells produced 742,934 barrels. Total

production of the field's lifetime stood at 140,644,377 barrels.

Source

Wikipedia |

Some of the information on this page

comes from the excellent book 'Baytown Vignettes', or 'The History of Baytown'

available at Sterling Municipal Library and the Baytown Historical Museum

located at 220 W. Defee.

|