|

||||

| The Ship | Their Story | The Crew | Survivors Organization | |

|

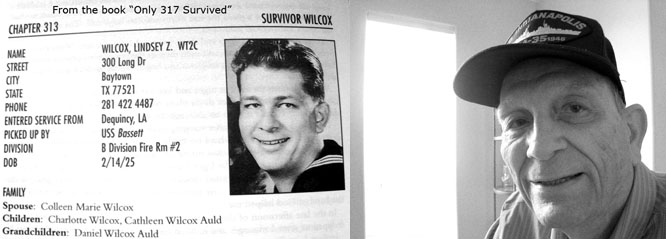

Mr. Wilcox passed away November 13, 2010. Rest in peace my friend. |

||||

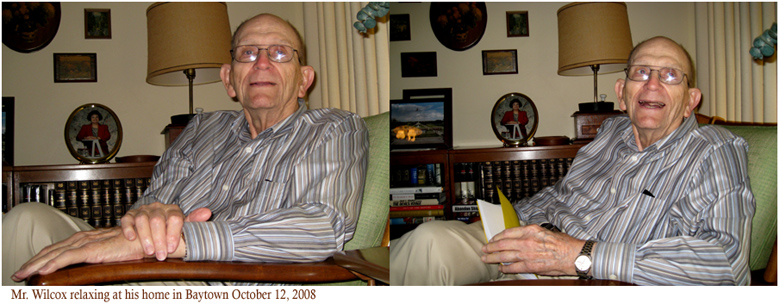

This week I sat down with World War II Veteran and Sailor, Lindsey "Zeb"

Wilcox and I must say he is bright-eyed and full of enthusiasm. He's a

striking-looking man with wide shoulders and I reckon he was no one to

truck with, back in the day. As a survivor of the USS Indianapolis

tragedy, he's certainly earned his place in history and the many books

written about the sad

event.

In short, he's a true war hero of the best kind and one of the folks

legends are made of. He's made of the fiber Baytownians love to brag

about and he represents all that is good about our city, state and

country. event.

In short, he's a true war hero of the best kind and one of the folks

legends are made of. He's made of the fiber Baytownians love to brag

about and he represents all that is good about our city, state and

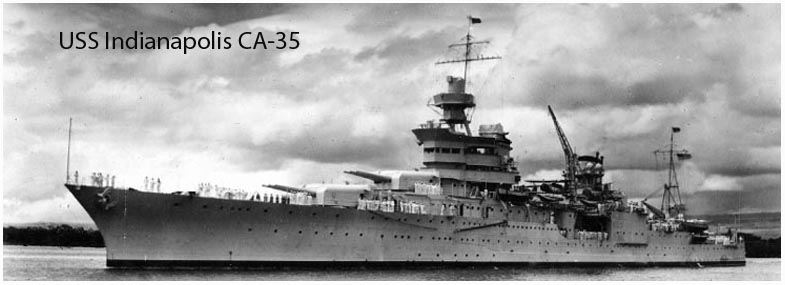

country.Today's article will be part one of three or more parts chronicling his life and the four hellish days he and his fellow Sailors and Marines endured, floating in the Philippine Sea after Japanese Submarine I-58 hit their Heavy Cruiser with 2 "fish" or torpedoes. The sinking of his ship is noted as "the worst single at-sea loss of life in the history of the U.S. Navy" and he lived through it all to tell us his story. The truth of the USS Indianapolis account was relatively unknown and kept mum until 1974 when the movie "Jaws" brought it to the public eye and this event, according to Mr. Wilcox allowed the survivors a chance to reunite and bring a sort of healing to their ranks. His memory is crystal clear and he is a walking encyclopedia of events, not to mention he is a thoroughly delightful man. The USS Indianapolis, after many engagements, was dispatched "at high speed to Tinian, Northern Mariana Islands, carrying the component parts and uranium projectile of the atomic bomb "Little Boy" which was soon to be dropped on Hiroshima", and delivered successfully, setting US Navy speed records. On July 30, 1945, while cruising at 17 knots towards Leyte, Philippines, the USS Indianapolis Heavy Cruiser, designated CA-35 and the flagship of Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance commanding the U.S. 5th Fleet, was sunk by two Japanese torpedoes, in less than 12 minutes. Two SOS signals were sent out, but through a tragic series of miscommunication, no one was aware of the sinking, or came immediately to their rescue So, that is the background of the ship and the war which made him a hero and now onto his story. "I was born in Dequincy, Louisiana. I was 16 when I graduated from Dequincy high school, which had only 11 grades at the time. The draft was in full effect as this was 1941 and some of my classmates, who were 19 and 20, were drafted even though they were in school. We knew about trouble in Europe and the Philippines, but we really didn't think it would involve our country". |

||||

|

|

||||

|

"I got a job in Baytown, Texas, while visiting my aunt, working for the Missouri Pacific railroad off of Harbor Street at the old depot. My job was a porter/trucker, which was sort of like a handyman/janitor and a freight man. I did a lot of cleaning work and I remember one particular day, we iced-down fish in a barrel for transport to a far away place". "At times, we would see as many as 50 Interurban electric cars a day on their circuit runs and I would ride a car to work and back to my aunt's house, next to the Trophy barbershop. I remember from her house to SH-146, Texas Avenue was a gravel road. I was 16 and since all young people were working jobs, I was as secure as anyone. My folks didn't worry; I was on my own". "About this time, I was bumped out of my union job by someone with more seniority and I bid on a job down close to Baton Rouge, a place on the Mississippi River called Anchorage. My job there was a Yard Clerk and since I didn't know anyone, I stayed at a place called "the Beanery", which offered room and board for $1.50 per day. My job was to check every RR car to make sure it had a seal on the door and since a giant RR switch yard is a scary place at night with hobos and all, sometimes it was a bit of a challenge. All I was given was a flashlight. If we caught a hobo, we would turn them over to the RR "Dicks" or detectives and we did catch a few". "The Beanery was a lively place and when we slept, the RR tracks were almost within arms length and when a train came through, it shook you almost senseless. The food was good though and later that place became a factory of sorts. They also processed sugar cane in the area. It was very loud there". "In Anchorage, there was a giant switch yard and RR cars would be ferried across the Mississippi River on a giant paddle wheel boat with two train-tracks laid on the deck. It would hold about 16 cars and since the river rose and fell with the tides, there was a pontoon bridge set up to hoist or lower train cars onto the paddle wheel. It was a sight to see. There were 4 or 5 old WWI Russian Steam engines set up with teams of men to operate them and they would move cars onto the boat for crossing. They were expert". |

||||

|

"880 men died, 317 survived and 79 remain with us" - Lindsey "Zeb" Wilcox - Baytown, Texas |

||||

"The railroad work taught me skills early on and I never went without a

job. I bid on an opening in my hometown of Dequincy,

Louisiana in 1941 as

a Roundhouse Clerk, which was the fellow that worked on the turnaround or

roundtable for locomotives, but lost it to another fellow who was also

promised the job. I was taken in by the Master Machinist even though I had

no family connections and was accepted for 65 cents an hour pay. I entered

the program in 1941 and was able to complete it after the war in 1948". Louisiana in 1941 as

a Roundhouse Clerk, which was the fellow that worked on the turnaround or

roundtable for locomotives, but lost it to another fellow who was also

promised the job. I was taken in by the Master Machinist even though I had

no family connections and was accepted for 65 cents an hour pay. I entered

the program in 1941 and was able to complete it after the war in 1948"."After 6 months, I was given a raise of a half cent an hour. Back then I paid $5 per month full hospital insurance too. I worked 6 days/48 hours a week and learned the trade at work and through lessons I received in the mail. One day in the shop, we heard the whistle blow, which meant to stop work. The tool room had a radio and we heard President Roosevelt talking about Pearl Harbor and just like that, we were at war. We were shocked a bit, but after a minute, we went back to work. We thought it wouldn't affect us and it was Washington's business". "We were aware of trouble in the Far East and Europe, but didn't think much about it, but times in America changed anyway and when I turned 17, I enlisted in the US Navy in New Orleans on what was called a "Kiddie Cruise". At that time, if you were under 18, your initial enlistment could only last until you reached 21 years of age. I boarded a train for San Diego and after 5 long days in a seat-only car, locked at both ends to prevent us from wandering around, we brand new sailors arrived for boot camp in the US Navy. I was in group 42-692 and for 8 long weeks we ate awful food and faced real mean drill instructors". "My instructors were all first class teachers though and we learned our jobs well. From there I went to trade school in San Francisco Bay at the Samuel Gompers building where I learned to be a Tool and Die maker. While in San Francisco we had Life Saving classes where we jumped off a 20 foot platform into the water wearing our "Mae West" life preservers, which had a 72 hour buoyancy lifespan. I didn't think we would ever need that training and anyway, I could swim like a fish, from back when I was first thrown in over my head by my first cousin, Louise Ross. I got where I could swim across Lake Worth up in Ft. Worth, while Louise rowed a boat beside me". "I was finally assigned to the USS Indianapolis. I was 18 and a Fireman 1st class, but I got sick with what was called "cat fever", which was nothing but being ran down and the standard treatment was 2 aspirin. They wouldn't let me board ship and it sailed, so they sent me by train to Bremerton, Washington. Another locked train car full of sailors with no sleeping quarters and a long trip. We played cards and told a lot of jokes and stories to pass the time and we had meal tickets so we could eat. My job in Bremerton was fire-watch on old cargo ships being converted to small Carriers. I had a key and I walked all over the ship, putting the key in clocks to show I was checking things". "About 3 weeks into this, I was sent up to Dutch Harbor, in Unalaska, Alaska to an old encampment the Army built called "tent city" and it was on top of a mountain, up a road about 5 miles. You could see the tops of the clouds up there and we 80 or so sailors split into 2 work groups and went down the mountain to do general work while we waited for our ship to arrive. If you missed the truck returning to camp, you had to walk up, so we didn't miss it. Next, we were sent to Kiska. Kiska is an island in the Rat Islands group of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska - no mans land. You could see Russia from there". "American P-38`s and P-51 Mustangs landed on corrugated steel runways there, as the whole island was nothing but volcanic ash. I worked food service for about a week and then the USS Indianapolis arrived and I shipped out for - San Francisco! Our great Portland-class heavy cruiser saw many engagements over the next 2 years and carried the first atomic bomb to be used in combat to Tinian Island on July 26, 1945. We were in the Philippine Sea when attacked at 00:14 on July 30, 1945 by a Japanese submarine. |

||||

|

"About

midnight I was relieved of duty and made my way to the deck to lay down,

when there was a tremendous explosion and fire came out of the forward

starboard and port passageways, extending half the distance of the

quarterdeck. We had been hit by 2 Japanese torpedoes and the ship was

listing badly, so I grabbed my life jacket and literally stepped off the

side of the ship into the water. I quickly swam about 50 feet away and

donned my "Mae West" jacket. The ship, all 615 feet of her, sank within 15

minutes of being hit".

"My group was taken to the hospital in Samar, a province

in the Philippines for 2 weeks and then sent to Guam. The war was over and

we came back to the States. I was honorably discharged when I turned 21,

at the Naval Air Station, New Orleans, Louisiana. I moved back to Dequincy

to be with my wife and finish my apprenticeship with the railroad. I've

never regretted my time in the US Navy or my time on the USS Indianapolis

- Still at Sea". |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Local man with historic WWII survival tale dies Lindsey �Zeb� Wilcox,

85, died Saturday, Nov. 13. The Baytown Sun A funeral service will be held Thursday for a Baytown man whose role in a World War II tragedy ensured his place in the history books. Wilcox was one of the survivors of the sinking of the USS Indianapolis, a heavy cruiser struck by two torpedoes fired by Japanese Submarine I-58 on July 30, 1945. The sinking of the Indianapolis in the Philippine Sea is noted as the worst single at-sea loss of life in the history of the U.S. Navy. Wilcox was one of the relative few who lived to tell about it. The ship had just delivered the world�s first operational atomic bomb to the island of Tinian on July 26, then was directed to head for the Leyte Gulf in the Philippines to prepare for the invasion of Japan. Unescorted, despite the captain�s request for battleship escort, the ship was midway between Guam and the Leyte Gulf when attacked. The ship went down in less than 12 minutes. SOS signals were sent out, but a series of miscommunications left the survivors on their own. No one was aware of the sinking (they thought the SOS was a Japanese ruse to lure ships into torpedo range) or came to the rescue. Of the 1.196 souls aboard, about 900 made it into the water in those 12 minutes. There were a few life rafts but most survivors wore a standard life jacket. Shark attacks began with sunrise of the first day and continued until the remaining men were finally rescued, almost five days later. Only 317 men were left alive by then. Wilcox was one of them. Born in DeQuincy, La., Wilcox graduated his high school at age 16 in 1941 and, while visiting an aunt who lived in Baytown, got his first job working at the railroad depot for the Missouri Pacific Railroad. Railroad jobs took him back to Louisiana and to Mississippi then, when the U.S. entered into World War II, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He was just 17. Trained as a tool and dye maker, he was assigned to the USS Indianapolis but missed his first cruise due to illness. He joined up with her again in Alaska and was part of her crew for two years, until the day the torpedoes struck. With many men injured, some bleeding, sharks were naturally attracted. They picked off men who sank underwater and those who strayed away from the larger group. Survivors later recounted the screams of men under attack. As more and more blood spilled into the water, more and more sharks came. Sharks were not the only threat. Many of the men gave in to the urge to drink saltwater, which they knew was no good, and suffered hallucinations, some even setting off to swim to some nearby shore no one else could see. During those five days afloat in shark-infested waters, Wilcox kept telling himself that he was a survivor and that he would survive. On the fourth day, he awoke from an uneasy sleep of exhaustion to find he had floated away from the rest of the sailors and was being pulled underwater by a couple of gray sharks. He came up fighting, he said, and apparently startled the creatures, that probably thought he was already dead. He swam through a mass of sharks to get back to the group. The next day, Aug. 2, the rescue finally began. Wilcox spent time in a Philippines hospital, then was sent to Guam at about the same time as the Japanese surrender. Wilcox was honorably discharged from the U.S. Navy when he turned 21. He said he never regretted his time in the Navy or on the USS Indianapolis, but he did suffer from recurring nightmares of being eye to eye with those sharks into his 80s. Wilcox was a member of Cedar Bayou Grace United Methodist Church, the Baytown Noon Lions Club and Cedar Bayou Masonic Lodge No. 321. He worked for many years for Solvay America and later for his own company, L.Z. Wilcox Sales. He is survived by his daughter, Cathleen Auld, and a grandson, Wil Auld. Wilcox was preceded in death by his wife Colleen Wilcox and a daughter, Charlotte. A visitation for Wilcox will be held from 5-7 p.m. Wednesday at Navarre Funeral Home, 2444 Rollingbrook Drive. His funeral service is set for 2 p.m. Thursday at the funeral home. Burial will be in Wilcox� hometown of DeQuincy, La.

|

||||

|

Harold J. Bray Jr.

Chairman; 400 Vista Court; Benicia, CA, 94510;

|

||||

|

|

||||